Cognac was the Scotch of the 1800s. What happened?

At sunrise in December 1861, with soldiers staving off pneumonia, Union General Robert H. Milroy led his troops across a snow-covered rocky meadow against an entrenched Confederate force. Even as the sun slowly flared to life amidst the iron clouds, the wind at the crest of Allegeny Mountain in Virginia’s western barrens kept up its relentless howling. Against the piercing gale, Union troops advanced throughout the morning. But as the clock tipped past noon, Confederate troops unleashed a barrage of artillery fire that drove the Union soldiers into retreat on Cheat Mountain. The war would continue — largely in stalemate — for almost four more years.

It’s hard to imagine a more different scene than what was happening five hundred miles to the north, behind the plate-glass windows of a saloon in cobblestoned, not-quite-quaint Manhattan. A certain Jerry Thomas was writing the nation’s first book on mixology.

“Professor” Jerry Thomas grew up on the Canadian border in Sackets Harbor, New York, before learning the craft of bartending in New Haven, Connecticut. From New Haven, he traveled west for the California gold rush in 1849 — one of the men whose toil gave rise to the name of San Francisco’s pro football team over a century later. He soon gave up mining and hung his shingle managing a minstrel show for the rough-shaven and rougher-languaged pioneers.

Two years later, he hung up his mining-camp boots and returned east to Manhattan. There, he opened up a number of saloons near the southern end of the island. At the time, Manhattan’s 500,000 residents traversed the city via a network of muddy roads, especially towards the less-developed northern end of the island . (In 1857, Frederick Law Olmstead finally landscaped some of this mud into what later became one of the more breathtaking sets for Home Alone 2: Central Park.) Professor Thomas’ south Manhattan saloons proved successful, affording him the opportunity to take up work as a bartending troubadour and travel to New Orleans, Chicago, and even Europe with a set of solid-silver bar tools.

By the time The Civil War began in April of 1861, Jerry Thomas had earned his famous nickname “Professor” and had begun work on the U.S.’ first ever cocktail book. Published as How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon Vivant’s Companion in 1862 and still referenced heavily today, over 150 years later, it seems unlikely the Professor knew quite how influential his book would eventually become. No matter to him, though, for he appreciated a well-prepared drink like few could, and simply wanted to spread his wealth of knowledge.

With the cold December day in 1861 pressing down on him, troops battling to the south, Professor Thomas imagined warmer climes, seeking to concoct a boozy tipple perfect for the spring that couldn’t come fast enough.

The recipe he arrived at was the Georgia Mint Julep. Originally styled for a cut-glass goblet, rather than a pewter cup, the recipe called for mint, sugar, crushed ice, and…not bourbon. Rather, the recipe called for brandy (and lots of it). Specifically, the julep-preparer was to summon 1.5oz of that most French of spirits, Cognac, into the glass.

Sacrilege, yes?

Not quite. At the time, bourbon hadn’t yet achieved its status as America’s Native Spirit. (That didn’t happen until Congress passed a resolution in 1964 declaring it so.) In fact, although people began to use the term “bourbon” in reference to a whiskey made mainly from corn, bourbon wasn’t really even a thing until around the 1870s. So Professor Thomas wasn’t as sacrilegious in omitting bourbon from his julep recipe as it seems at first glance.

Yet rye whiskey was a thing and had been so since the late 1700s. A very big thing. No less a figure than George Washington opened the nation’s biggest rye whiskey distillery in Mount Vernon after his tenure as President ended, to capitalize on rye’s popularity.

So why did Professor Thomas opt for Cognac in his original Georgia Mint Julep recipe, rather than a spirit developed closer to home?

In a word: audience. Thomas was writing a book on cocktails, a relatively recent invention for a rather upscale clientele who could afford both the showmanship of mixology and the spirits included in the final product of such theatrics.

In the mid-1800s, whiskey didn’t exactly have a reputation for quality — Scotch was especially haunted by poor reviews after many Scottish distillers had abandoned their pot stills in favor of the more efficient column still. France still had a firm grip on luxury culture of the day, especially its world-renowned wine and distilled spirits, including Armagnac, Cognac, and Calvados. Of all the spirits, Cognac received the most acclaim.

Since the 1400s, Dutch traders importing French wines had concentrated French wine into distilled spirits form and stored it in oak casks for the rough voyage from the southern France to Amsterdam. Once at port, the traders would add water to this distilled wine (or “brandewijn” — burnt wine in Dutch) to reconstitute the wine spirit into wine.

French vineyard owners took note. As taxes on wine increased, they diverted some of their plantings to more acidic grapes, most notably the Folle Blanche varietal. The growers and Cognac producers built long houses called chais along the Charente River to store French oak casks of newly double-distilled Cognac. (Whisk(e)y was late to the game, only beginning to receive barrel treatment in the mid-1800s.)

French distillers’ Cognac matured in these damp riverside conditions slowly over a number of years, driving up the price of Cognac with each passing day. Such lengthy maturation conditions, along with the finesse and complexity of the cask-aged Cognac and lack of high-end alternatives gave Cognac’s elevation to luxury status an air of inevitability.

The rich and famous on the U.S.’ eastern seaboard joined in the fun, quaffing Cognac at galas year-round. Honest Abe drank it, albeit in small amounts. President Chester A. Arthur downed it (and its teetotal cousin, wine) two decades later.

Conspicuous consumption had never gotten such a rush of rancio to the head.

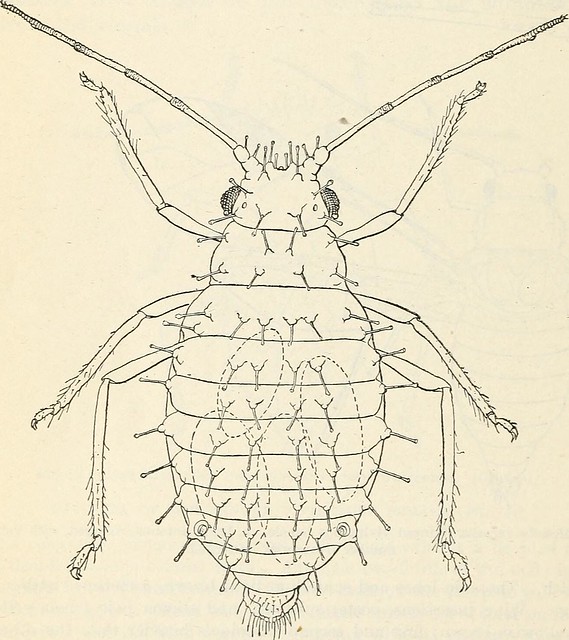

But in 1872, something mysterious began to happen. Grapevines in France inexplicably died. No one knew why. Vintners labeled it “wine fretters”, and fretting they did. Scientists soon discovered the plague was a tiny, yellow insect related to the aphid — they named it Phylloxera vitifoliae. (That part of the species name rhymed with pox seems most fitting.)

Phylloxera's cousin, the aphid.

The supply of French wine and Cognac plummeted throughout the rest of the century. Cognac-makers ripped up the old Folle Blanche vines and planted a new, Phylloxera-resistant varietal, St. Emilion. But Cognac would never recover its prowess as the luxury tipple of choice.

Whisk(e)y, especially Scotch, rose to the occasion, filling the luxury drinks void that Phylloxera had left. Even during the World Wars when millions of soldiers from around the globe crossed French soil, whisk(e)y retained its edge. An edge it maintains to this day.

The irony of the whole epidemic is that the insect only found its way to European shores when British scientists brought cuttings from U.S. vines to the United Kingdom for study. Hard to believe that a careless, cross-Atlantic transplanting of grapes led to a century-plus depression for Cognac.

But things are looking up for Cognac and the brandy category in general. (Cognac is a sub-category of brandy — which is a distilled spirit made from fruit, usually grapes.) After declines in the years leading up to 2015, Cognac sales finally rose at a fast clip last year. Many U.S. journalists have begun speculating on whether U.S. apple brandy may likewise begin an ascent. (President Reagan served the most famous U.S. brandy — Germain-Robin — to President Gorbachev during their many visits.)

These are welcome signs of vitality from a quality category that has received neglect for too long. As the Union troops proved a century and a half ago, a few down years don’t always spell doom. Professor Thomas would likely agree. We certainly do.

— — — — —

(1) The aggressive recipe also calls for 1.5oz of peach brandy.